I’m back from Maternity Leave to continue my series on cosmology and culture. I would like to dedicate this article to Wal Thornhill. His recent passing is a profound loss for so many of us. Discovering the electric universe and meeting Wal years later, changed the course of my life, and career. As a social scientist with a lifelong personal interest in cosmology, I had long given up hope of understanding the universe because big bang cosmology made no sense to me. Then I learned about the electric universe. It led me down a new path of research and discovery, and to the answers that big bang cosmology had failed to provide.

It also led me to the ground breaking work of Thomas Kuhn, which allowed me to access the world of science through my own background in critical analysis. In light of Wal’s passing, it is more important than ever to highlight the implications of Thomas Kuhn’s work, and what it reveals about the true nature of predominant Science—and cosmology in particular. Understanding the nature of Science, allows us to appreciate just how important—and how courageous—Wallace’s work and legacy are.

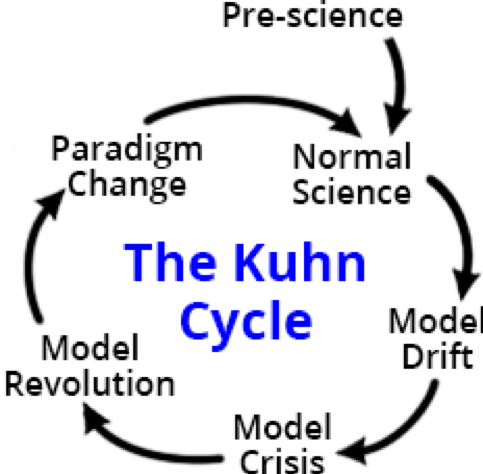

Central to my series has been the argument that cosmology is presently at a crisis point and headed towards an inevitable paradigm shift or revolution; and, secondly, that the Electric Universe Model has an important role to play in the cosmology of the future. The term paradigm shift underlies much of this work. It was popularized through Thomas Kuhn’s seminal work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Since the publication of this book in 1962, there has been much misunderstanding and/or misrepresentation of its overall thesis.

It is important to note that Kuhn did not set out to write the book he eventually ended up with. He originally set out to write about the history of science, and discovered something unexpected about how science is done along the way. In the process of exploring the history of scientific change, Kuhn discovered that institutionalized Science operates much differently than how we have been led to believe it does.

The larger and deeper thesis of Structure is that predominant Science, ultimately, does not do science the way it claims to, meaning that institutionalized science is not absolutely empirical. Through a historical study of science, Kuhn discovered that once a scientific paradigm becomes entrenched and institutionalized, it often becomes dogmatic, hegemonic and unyielding to falsification and change. Almost by accident, Kuhn’s book became an interrogation of Science in and of itself. And it paints an unflattering but arguably more realistic picture of Science than the idealized or utopian image of Science as presented by, for instance, one of Kuhn’s biggest opponents, Karl Popper.

Popper was an Austrian-born philosopher with a doctorate in psychology.[i] “For Popper the ‘core scientific ethic’ was falsifiability– meaning that “all knowledge, at all times, should be exposed to constant and deliberate criticism.”[i] This is what distinguishes science from non-science, according to Popper. Kuhn would whole-heatedly agree with Popper: Falsifiability should be the core scientific ethic or principle. The problem is that, in reality, or, in practice, it is not, and this is what Kuhn’s work reveals.[ii]

Another critic of Kuhn was Austrian-born philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend. Feyerabend is most known for his book Against Method, wherein he argues that there are no universally valid methodological rules for scientific inquiry, and champions theoretical pluralism.[ii] Both Feyerabend and Popper accuse Kuhn of glorifying normal science and hiding behind it. If we recall from previous work, normal science is the stage where a field or discipline has a scientifically based model of understanding that works. Feyerabend and Popper accuse Kuhn of wanting science to always stay at the stage of normal science and, therefore, of resisting paradigm criticism and change.[iii] This is a blatant mis-reading and misrepresentation of Kuhn.

Kuhn did not insist that science should not progress beyond the non-problematic stage of normal science. On the contrary, he revealed (and lamented) that scientists tend to insist that they are doing normal science—i.e., that their model and paradigm has no holes or problems—long after the model has started to drift and fail. His book problematizes the fact that, in practice, science attempts to force a Model to stay at the normal stage—i.e., “business as usual”—despite mounting anomalies and contradictions that the Model cannot adequately address. And this is especially true in cosmology. As the highly esteemed philosopher of science, Ian Hacking, points out in his introductory essay to the 2012 addition of Kuhn’s book, big bang cosmology is “full of outstanding problems pursued as normal science.”[iv]

This is the crux of the problem. And this is why Kuhn’s work is indispensable for any critical analysis of the present state of cosmology. With respect to cosmology, Kuhn’s findings about the reality of how science is done, are even more relevant today than they were in 1962. As Hacking points out, at the time of Kuhn’s writing, there were two competing cosmological models. But, today, Big Bang cosmology has a monopoly on truth.

If we recall from previous shows, after Normal Science the predominant model of understanding starts to drift, due to the accumulation of anomalies and phenomenon that the model cannot explain. At this stage (called Model Drift), one might reasonably assume that the predominant model has the opportunity to self-correct and re-examine its foundational theories and assumptions and/or explore alternative explanations, if needed. However, this rarely happens. Rather than address the problems directly and re-examine their premises and assumptions, scientists working within a dominant model focus on patching the model up and attempting to manage the problem. This process of perpetual patchwork creates more problems and eventually leads to crisis and model breakdown.

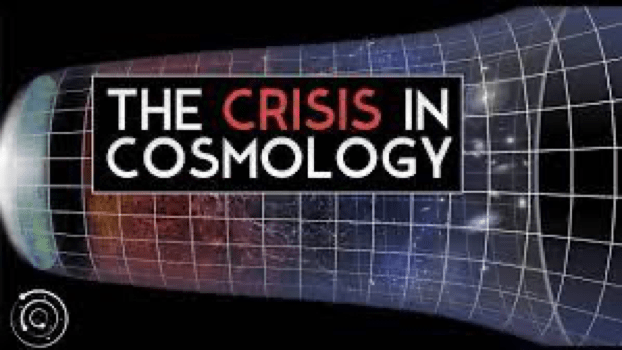

As we demonstrated in several previous shows and articles, this is where Standard Cosmology presently finds itself–at the stage of model crisis and breakdown. Cotemporary cosmology is in deep crisis, and the awareness of the crisis is increasing every day. Mainstream cosmologists openly use the word crisis to describe the present reality, and mainstream media is full of headlines that suggest that cosmology is in deep trouble.

As physicist and science writer Eric Lerner points out, in 2019 there were 130 media references to the crisis in cosmology; which marks an exponential increase from the mid-2000s, when there were only twelve references a year.

The crisis centers on new information, measurements or findings that undermine or contradict, the major principles, assumptions, or expectations of the Big Bang Theory in some way. These include new information or measurements that suggest: that the universe is not expanding as we thought or at all (known as the Hubble Tension); that the universe is round and not flat; and, that the universe is more or less homogenous than we thought. There are also numerous foundational predictions of the Big Bang theory that have been contradicted by abundant observation— including various observations and accurate predictions made by Electric Universe proponents such as the late Wal Thornhill.

The most recent problems have been sparked by even more contradictory measurements and observations coming back from the James Webb Space Telescope. In a recent video, American physicist Michio Kaku states that “the James Webb Telescope is upsetting the apple cart. All of a sudden we realize we may have to rewrite all of the textbooks about the beginning of the universe” And in another recent video, online science channel, Science Time 24, explains that the James Webb Space Telescope has discovered six ancient galaxies that shatter our understanding of the universe.

Beyond these individual contradictions and discrepancies, the larger and deeper crisis center around Standard Cosmology’s underlying narrative and its very approach to cosmology. As theoretical physicist and physics commentator Sabine Hossenfelder aptly pointed out at a recent symposium entitled “What is Wrong with Current Physics?”, a good scientific explanation should be as simple as possible and you shouldn’t add any unnecessary assumptions, no matter how much you need them to justify your hypothesis. Indeed, simplicity is one of Kuhn’s main criteria for model revolution and paradigm change. Hossenfelder notes that all of the stories and assumptions of current physics are basically “creation myths written in the language of mathematics.” Hossenfelder concludes that while we don’t know if big bang creationists are wrong, we also cannot say that they are right because: “they just add this unnecessary structure at a time where we don’t have any data.”

At the same symposium, Eric Lerner argues that the big bang is a theory that “requires imaginary entities that are made up after the fact.” Lerner holds that without imaginary concepts and entities such as inflation, dark matter and dark energy the theory collapses. These concepts were introduced “to prevent or overcome severe conflicts with observation.” For instance, as Lerner explains, without dark energy, under the big bang theory, the universe would be younger than the Milky Way galaxy. And without dark matter, the universe wouldn’t form any clusters or galaxies at all. Lerner concludes that: “you can’t say that you want a pure big bang without all this fairy dust.” Lerner says we should look to alternatives that rely on verified laboratory evidence, and points to his own work on plasma phenomena and laboratory fusion devices as an example.

At an April 15 iai symposium entitled “Beyond the Darkness–Dark Matter: A Baseless Hypothesis?” philosopher Bjorn Ekeberg reminds us that there is a lack of empirical evidence supporting dark matter. As the panel’s host, scientist and professor, John Joe McFadden, points out, “decades of searching have so far revealed exactly zero dark matter particles, and now some cosmologists are starting to look for alternative models of the universe that don’t posit dark matter”

For Eric Lerner, the real crisis in cosmology is that the big bang never happened, a sentiment that is echoed by Eclectic Universe proponents. Whatever alternatives one chooses to explore, it is becoming increasingly apparent that current cosmology and astrophysics are in deep trouble, or, to use the language of Thomas Kuhn, are presently at a crisis point.

At the Crisis Stage, scientists continue the patch work but also go beyond it, inventing ad hoc revisions, in an effort to deflect or mask the mounting contradictions and inconsistencies. With respect to the crisis in Standard Cosmology, scientists are doing this and much more.[v] Many working within the Standard Model also double down on the model’s contradictions and inconsistencies, and have even gone as far as to celebrate them and characterize them as exciting opportunities for future research. One example is a claim made on the show PBS Space Time. In the video, the host argues that while contradictory measurements on how fast the universe is expanding—i.e., the Hubble tension—are getting worse, this is actually “exciting” because the growing contradiction and crisis opens up new avenues for research. One can imagine that if and when the James Webb telescope brings back even more contradictory measurements and findings—that the big bang happened much earlier than they originally thought, for instance?—that big bang scientists will again move the goal posts, giving them enough patch work to keep them busy—and in business—for generations to come!

Overall, emphasising patchwork and ad hoc extensions over empirical problem-solving, doubling down on inconsistencies and contradictions, celebrating such contradictions as wonderfully weird opportunities for future research, all suggest that, as the predominant model begins to drift and fail, scientists stop honouring the scientific method (i.e., stop acting empirically) and become more concerned with keeping a broken model afloat.

This die-hard reluctance to question a failing model flies in the face of falsifiability, which, as we recall, according to Karl Popper, is the underlying ethic of science. The fact that science shuns falsifiability (a fundamental principle) when it is most needed begs the question why? Either science is not what Popper claims it to be or there is something else at play, or both.

When viewed from a socio-political perspective, one begins to see power and hegemony at play. And this is what Kuhn’s work implies. What begins to emerge at the Crisis Stage, is the idea that institutionalized and entrenched scientific models—and those working within them and the official channels that fund them—tend to become more concerned with not relinquishing power and self-preservation than empirical observation, problem-solving, and the pursuit of scientific truths or new knowledge. The main take away from all of this is that entrenched Science does not do and/or is not willing to do what it claims to do—i.e., test its theories and hypotheses empirically and change course when needed.

Popper and others were infuriated by such findings, not least because it tarnished the idealized and noble image of Science that had been espoused up until the publication of Structure. It is worth re-stating that Kuhn also held Science to a higher standard, and hoped for it to conduct itself empirically. Kuhn did not set out to tarnish the image of science. He was a trained physicist after all. But as any truly empirical scientist can attest to, scientists often end up with very unexpected results once they enter the lab and conduct their experiments and analyses. In the case of Kuhn, his lab was history itself, and as a true empiricist, he was not willing to deny or skew his findings, no matter how unpleasant or inconvenient they may be to the status quo. And he suffered tremendously for his integrity. Since the publication of his book, Kuhn has been attacked, personally and professionally, for shining an unflattering light on the nature of institutionalized science.

To the Poppers of the world, Kuhn is a heretic. Rather than attempt to refute Kuhn’s thesis Popper, Feyerabend and others attack him for having the audacity to shine a light on Science. To his opponents, one of Kuhn’s biggest crimes was making conclusions—and what they perceive as predictions—about how Science operates based on its history. In other words, they condemned him for being historical. For his critics “historicism was not just wrong, but immoral – and insofar as Popper and his followers saw historicism hugged-tight within the concept of normal science, Kuhn was also immoral.”[vii]

It should be noted that historicism is defined as “an approach to explaining the existence of phenomena, especially social and cultural practices (including ideas and beliefs), by studying their history, that is, by studying the process by which they came about.”[viii] In his book, Kuhn looked at the history of science and scientific progress and made some observations about how science changes and progresses. It seems strange, if not duplicitous, to condemn the author of a book on the history of science for using history in his analysis. It is an Orwellian act that condemns historicism for philosophical reasons—that date back to philosophical disagreements from antiquity—when Kuhn is merely using history as a method. This is philosophical straw man argument at best. And it begs the question; why not just refute Kuhn’s findings?

Rather than refute Kuhn’s findings, his critics condemn him for arriving at them in the first place, in what appears a case of “shoot the messenger.” that For instance, in his critique of Kuhn, American social philosopher and hardcore proponent of transhumanism[iii], Steve Fuller, accuses him of presenting an image of predominant or institutionalized Science and Science Education that resembles a “mini-Vatican”, a “Royal Dynasty”, and, even, “the Mafia.”[ix] For opponents such as Steve Fuller, Kuhn is guilty of presenting a predominant paradigm as “an irrefutable theory that becomes the basis for an irreversible policy.” As Australian-born writer, teacher and academic, Jed Lea-Henry, maintains, in Kuhn’s depiction of paradigms:

“the community of researchers create science in their own image: setting the standards, recruiting people who will continue with those standards, and then hovering as divine judgment over how well they go about doing this. It is a mini-Vatican, a state unto itself where the only safeguards are those which they create….It is a horribly circular world, where no-one is ever accountable to anything, or anyone, outside of themselves.”[x]

Kuhn never said these exact words, but this is what many deduce from his book. It is interesting to note that Kuhn’s detractors do not attempt to disprove this negative view of Science; they simply complain and condemn Kuhn for having the nerve to come to such a conclusion, in the first place, and for using historicism [xi] to get there. This begs the question: If Kuhn is wrong, why do they not refute his findings.[xii]

Whether his critics characterize his finding as historicist, predictive or immoral, given the current state of institutionalized Science—and the current crisis in Standard Cosmology—I think it is fair to say that Kuhn’s findings still hold and are presently more valid than ever. Sorry Popper et al, but if it looks, sounds and acts like a duck …then Kuhn must be right.

The unflattering image of Science depicted in Kuhn’s work could easily be applied to other institutions such as Politics and Political Education. I studied political science as an undergrad and wrote as a political analyst for many years. I can attest to the self-preserving and circular nature of both mainstream politics and political theory. With respect to the latter, western political philosophy often seems more concerned with preserving the dominant sociopolitical order than with rigorous investigation. For instance, in the book The End of History and the Last Man, American political scientist, Francis Fukuyama, argues that liberal democracy has proven to be a fundamentally better system than any of the alternatives, and, therefore, there can be no advancement from it to an alternative system. As such, liberal democracy represents “the end of history,” in that this form of government is the final form of government for all nations.[xiii] In other words, liberal democracy is the best and final political paradigm, and, thus, there can be no alternatives, ever. Talk about arrogance and self-interest. Who’s being predictive now?! How can anyone that calls themselves a political scientist declare that history ends with their particular model of government? Are we to believe that the fact that Fukuyama is American, and, that America is the dominant and hegemonic liberal democracy in the world, has nothing to do with this line of reasoning.

Fukuyama’s circular logic is similar to that of proponents of the Big Bang theory. For instance, in an article entitled “Could the Big Bang Be Wrong?,” Corey S. Powell concludes that: “We have a lot to learn about our place in nature’s grand scheme. But we can be quite confident that, wherever future theories and discoveries take us, the Big Bang will be a part of the picture.”[xiv] Given Powell’s conclusion statement, we can assume that the answer to the article’s title question, “could the Big Bang be wrong,” is a resounding no. Similar to Fukuyama and liberal democracy, this article more or less implies that the Big Bang marks the end of history for cosmology; that there can be no advancement from it to any alternative theory–since it is the best one to ever exist, and, that can ever exist. If this is not an example of “an irrefutable theory that becomes the basis for an irreversible policy”—the characterization of dominant paradigms that Kuhn’s critics condemned him for arriving at—then I don’t know what is.

We see this outside of cosmology as well. For instance, the unquestionable greenhouse theory of atmospheric change currently directs everything from city planning to corporate investment. In the current era of “green investing” and “sustainability,” companies are mandated—through government regulations—to invest in a manner that reflects dominant western ideologies on the environment, weather changes, and environmental sustainability.[iv] One only has to look at the city planning initiatives known as Green Cities and, more recently, “Fifteen Minute Cities.” These are political acts and directives. When policy demands consensus in science and dictates what type of science is acceptable, and when official science is happy to oblige, we are no longer dealing with (just) science.

This suggests that, in addition to similarities in practice, there is a growing relationshipbetween institutionalized Science and institutionalized power. If scientific change was merely about shifting scientific worldviews that come about due to model falsification, then why was Galileo imprisoned for life for his new perspectives on cosmology. And why was Socrates executed by the powers that be, for his. Both of these men promoted opposing or alternative cosmological and philosophical ideas that undermined the dominant power structures (and ideologies) of their time; and both were punished severely for it. Historically, ideas that defy power or the status quo are undermined, while those that bolster it, are promoted–through government funding, illustrious awards and careers, the mainstream media, etc.

This has everything to do with power and the unyielding nature of dominant institutions, including the Institution of Science. Once a model becomes as deeply entrenched and institutionalized as well as as heavily funded and supported, as the Standard Model is, for instance, it becomes perceived as too big to fail. In other words, there is so much invested in the model—and the illustrious careers and institutions that both supports it and relys on it—that the model cannot be wrong. There is just too much at stake. Thus the focus shifts from scientific integrity to maintaining a model’s authority.

It is worth noting that since the Industrial Revolution, Science—and scientific research and funding—has become increasingly specialized and linked to capitalist enterprise and Big Business. In the field of cosmology, almost all present-day funding and peer review publications are given to scientists working within the Big Bang theory (see Eric Leaner’s video The Crisis in Cosmology). For instance, as Eric Lerner explains, his alternative research and writings are habitually denied publication and censored from various science websites. Lerner is known for his 1991 book entitled The Big Bang Never Happened, which promotes Hannes Alfvén’s plasma cosmology instead of the Big Bang theory. Lerner laments that in present-day cosmology; anyone working outside of the Big Bang theory is deemed “stupid” and denied a platform or dissemination.

This is a good illustration of why Kuhn argued that science is forced to change. When Kuhn used the word revolution he was not ignorant of the gravity or connotation of that word. Revolution is inherently forceful; and is often born of tyranny and crisis. Those that dismiss his primary thesis—and its critique of entrenched or institutionalized Science—are, therefore, either ignorant of its meaning or intentionally denying its broader implications.

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is a paradigm shift in and of itself insofar as it radically changed the way we view and understand Science. This is why it angered, and continues to anger, so many mainstream scientists. Its larger thesis is a commentary on how Science is done; on how we as humans carry it out. Essentially, the book revealed that, at the Institutional level, Science often ceases to be empirical and becomes unyielding—preventing its own progress. Structure ultimately lays bare the difference between Science in theory and Science in practice. It dispels illusions about entrenched Science as purely objective or altruistic and exposes its tendency towards dogma and hegemony as well as its deference to authority. This is something we witnessed during the pandemic, with medical professionals putting deference to authority before concern for patient care and well-being.

As a society, we tend to hold Science to a higher standard. Unlike Politics or the Media (and other institutions), we are led to believe that Science is purely objective and not self-interested or corrupt. Given this idealized view of Science, it can potentially be used as a tool to influence or manipulate people. In addition, critics of official scientific narratives may be subject to ridicule and public shaming, and increasingly, even risk being cancelled. Ironically, this goes against falsifiability, Karl Popper’s “core ethic of science,” which, as mentioned earlier, is the notion that “all knowledge, at all times, should be exposed to constant and deliberate criticism.”[xv] That predominant Science often opposes and restricts falsifiability—as is presently the case with cosmology—suggests that there is a power component at play at the level of institutionalized science that simply cannot be ignored.

Kuhn’s paradigm shift cycle is presently unfolding right before our eyes. The current crisis in cosmology proves this; and has vindicated Kuhn from beyond the grave. Mainstream cosmology even uses the word crisis—which is one of Kuhn’s definitive stages—to describe its present reality. At the same time, Standard Cosmology is unwilling to address the crisis in a meaningful way, and is not open to new ideas or falsification. These are tell-tale signs of the unyielding, dogmatic and self-preserving nature of institutionalized Science.

For this reason, Kuhn’s work is even more relevant today; and is indispensable for understanding the true nature of predominant science, and the present state of cosmology, in particular. One cannot ignore the similarities between Wal Thornhill and Thomas Kuhn. Both of these great thinkers were unwaveringly empirical in their search for truth, and both dared to report their findings with honesty and integrity; no matter how controversial it made them.

Notes

[i] https://www.jedleahenry.org/popperian-afterthoughts/2021/5/27/karl-popper-vs-thomas-kuhn

[ii] Given his emphasis on empirical falsification as the main driving force and ethic behind science, it is not surprising that Popper was angered by Kuhn’s findings. While falsification is what Science claims to be driven by in theory, Kuhn found that, in reality, once Science becomes entrenched/institutionalized, it resists falsification and change. In other words, Structure trashed Popper’s official version of how science conducts itself, and he was not happy.

[iii] See the quote by Feyerabend for more on this: https://www.jedleahenry.org/popperian-afterthoughts/2021/5/27/karl-popper-vs-thomas-kuhn

[iv] Hacking, Ian. cited in Kuhn, S. T. (2012). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Fourth Addition, p.x.

[v] It should be noted that when I mention science hereafter I am referring mostly to cosmology.

[vi] As we discussed elsewhere, Einstein’s theory of relativity had impacts far beyond science, normalizing and promoting paradox, and the acceptance and celebration of weirdness, in the public imagination. See–https://www.thunderbolts.info/wp/2021/04/10/not-if-but-when-cosmology-in-crisis-the-coming-paradigm-shift-part-2/

[vii] https://www.jedleahenry.org/popperian-afterthoughts/2021/5/27/karl-popper-vs-thomas-kuhn

Note: Karl Popper was a philosopher of science. It is strange that a philosopher would condemn another philosopher—especially one with a background in physics—for using history in his analysis. After all, where would philosophy be it did not draw on history.

[viii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historicism

[ix] See https://www.jedleahenry.org/popperian-afterthoughts/2021/5/27/karl-popper-vs-thomas-kuhn

[x] Lea-Henry and Fuller cited in https://www.jedleahenry.org/popperian-afterthoughts/2021/5/27/karl-popper-vs-thomas-kuhn

[xi] For using history to describe how Science behaves, Kuhn was accused of being “predictive” in his analysis.

[xii] It is interesting to note that Popper pulled out of his one and only

[xiii] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_End_of_History_and_the_Last_Man

[xiv] https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/could-the-big-bang-be-wrong

[xv] Karl Popper cited in https://www.jedleahenry.org/popperian-afterthoughts/2021/5/27/karl-popper-vs-thomas-kuhn